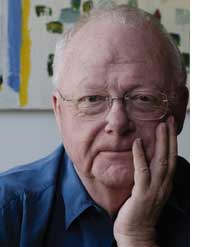

Andriessen: interview about new monodrama Anaïs Nin

Louis Andriessen discusses his new monodrama Anaïs Nin, premiered in Siena in July, touring the Netherlands in November and travelling to Germany and the UK next year.

How did you discover the writings of Anaïs Nin?

Strangely, I knew about the father Joaquín Nin, who was a famous pianist and composer, before the daughter. This was because my own father’s music collection contained some of Nin’s piano pieces and his arrangements of Spanish songs. Only later in the ’60s did I learn about this crazy girl in America when her diaries hit the news because of their sexual frankness.

How did you select the texts for the new work?

I had the framework of a half-hour theatre piece, so needed to home in on suitable texts. In the ’90s the unabridged version of Anaïs Nin’s journal Incest was published, covering the period 1931-33 when she lived in Paris with her mother. The sexual relationship with her father, who showed up after an absence of about 20 years, was clearly to be central to my piece, and this particular part of her journal has lots of beautiful and poetic writing about this. It also provided the necessary context with material about her other lovers at that time, the actor Antonin Artaud, the psychiatrist René Allendy and the writer Henry Miller.

With our distance from the interwar Parisian literary hothouse, what is the importance of Nin for you today?

I’m not so interested in the psychological or the literary aspects of Nin. What I like is the way she flirts with history and fiction as Nabokov does. It is not important whether her narrative is true – the reality of it is not relevant. Her power is that she creates a life through writing. So, she is like the composers I love who make allusions to history and work with pre-existing music. Stravinsky is always the best example, but even Mozart admitted stealing from Papa Haydn. This creative dialogue with the past, which I share, is not a plea for conservatism – it is quite the opposite.

Nin said that “Music melts all the separate parts of our bodies together”. Do you view music as an erotic artform?

There is no direct relationship between music and the erotic. It is more to do with mood and sentiment (but not sentimentality!). There are more literal analogies with language, where the listeners can feel close in their own way to what is being described, so I have never avoided erotic subject matter in my works with text because this is part of life. However you cannot set up such a direct correspondence with music because it is so polyvalent – you always have different possibilities presenting themselves at the same time. If you think of melody and harmony, a leading note can go down as well as up, and this ambiguity, which only makes sense in tonality, is important in my composing.

How does the monodrama project itself theatrically?

I’m exploring a form of narrative to create a distinctive theatrical world, providing context through words, music and film. Cristina Zavalloni is seen and heard as Anaïs Nin on stage and on film. There is no archive footage, but I’ve created film fragments which hint at the period and setting, and allow her lovers Artaud, Allendy and Miller to appear as characters, with their words recorded by performer Han Buhrs. It is only Nin that sings on stage: of her passions, of her incestuous love affair with her father, but ultimately of her loneliness and perpetual hunger.

How was the vocal part written specifically for the voice of Cristina Zavalloni?

We’ve worked together a lot but I think this is our best collaboration so far because Cristina is so perfectly suited to do the role of Anaïs Nin. She has an amazing ability to rapidly switch moods and styles, which comes from her versatility with different musical languages, from medieval to contemporary. When writing for her voice I don’t think of it in lyrical terms – it is more like an expressive medium, a theatrical presence, a narrative force, a volatile personality.

Are there special features of the instrumentation?

The fact that the eight Nieuw Amsterdams Peil musicians, who would give the premiere, perform without a conductor set me some technical challenges. They are musicians who play difficult contemporary scores, are willing to put in long rehearsals and really listen to each other. It will be interesting to hear the piece when performed by other ensembles usually with conductor, including the London Sinfonietta. The choice of instruments was influenced by the chosen diary’s period of the early 1930s. This explains the use of saxophones, clarinets (Sidney Bechet, Coleman Hawkins) and percussion (drumset including hi-hat, guiro etc). So the soundworld for Anaïs Nin is like a little circus band and the music closely tracks the irony, despair and passion of this many-sided and brilliant woman.

Andriessen

Anaïs Nin (2009-10)

Monodrama for singer, ensemble and film

Commissioned by London Sinfonietta,

Nieuw Amsterdams Peil and the

Accademia Musicale Chigiana

Performances, all with Cristina Zavalloni, include:

4 November (Dutch premiere)

Muziekgebouw aan’t Ij, Amsterdam

Nieuw Amsterdams Peil

6 January 2011 (German premiere)

Kurtheater, Bad Kissingen

Nieuw Amsterdams Peil

14 April 2011 (UK premiere)

Queen Elizabeth Hall, London

London Sinfonietta

> Further information on Work: Anaïs Nin

Photo: Francesca Patella