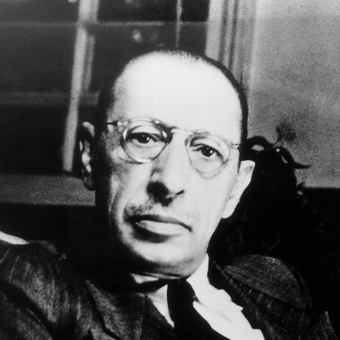

Igor Stravinsky

Introduction to Stravinsky’s music

by Stephen Walsh

With the close of the twentieth century, it seems clear that Igor Stravinsky has emerged as one of its two or three greatest composers, and he will certainly be remembered as its most many-sided. A study of his work automatically touches on every significant tendency in the century’s music, from the vibrant neo-nationalism of the early ballets, through the more abrasive, experimental nationalism of the First World War years, the neo-classicism of the twenties, thirties and forties, and the studies of old music which produced masterpieces like Agon and the Canticum Sacrum in the fifties and led on to a highly personal reinterpretation of the serial method of Schoenberg. Along the way, Stravinsky came into contact with every kind of mainstream and fringe tendency, from the noisy Futurism of pre-Mussolini Italy, to the popular music of forties Hollywood and the spiky avant-gardism of Boulez and Stockhausen: and he took something, however obliquely and transformed, from all of them. But, though a mirror of his age, he never let it dictate his way of writing. Through all the changes of ‘manner’, the surprises and renunciations of the natural modernist, he remained in essence the same kind of composer from Petrushka to the Requiem Canticles.

Stravinsky established himself from the start not just as an innovator, but as one for whom clarity, directness and listenability were prime virtues. Petrushka was immediately popular, even though new in many aspects of rhythm and texture; and while early audiences were dis-concerted by the sheer ferocity of The Rite of Spring, they soon responded to its physical excitement and idealised primitive simplicity. The composer got tired of the extravagance of these early works, and went through a more experimental phase in which he explored on a smaller scale and in an austere and intimate style some of the more suggestive aspects of The Rite. These war years, framed by the Three Pieces for String Quartet and the Symphonies of Wind Instruments, marked the extreme point of Stravinsky’s radicalism. The new stylistic self-consciousness, as heard in those prototypes of neo-classicism, Mavra and the Octet, seems to express a need to reconnect with traditional music, without abandoning a modernist stance.

For thirty years Stravinsky wrote works that pretended to be tonal, in sonata or concerto form, classically phrased, scored ostensibly for a ‘standard’ Bach or Beethoven instrumentation; or works that pretended to be in a popular style, like the Scenes de Ballet or the Ebony Concerto; eventually even a pseudo-Mozart opera, The Rake’s Progress. So when, after the Rake, he again looked for some basis for renewal, he started from the purest elements of tonal language. The Cantata contains ideas of a proto-minimalist simplicity, though it complicates matters in its long, canonic central movement. But serialism, for Stravinsky, never meant tortured Viennese angst of the Schoenberg kind. He was fascinated by Webern’s highly arithmetical mind and repressed sensuality. But not even numbers – perhaps least of all numbers – could crush his natural feeling for rhythm and movement, his love of colliding sonorities, or his sense of underlying harmony; and even at its most recondite (in the Movements or the ‘Huxley’ Variations) his late music always achieves escape velocity. Even when it sometimes baffles the mind, it always excites the corpuscles.

Stravinsky had many publishers, starting with Jurgenson in Moscow and Schott in Mainz. After the Second World War, Boosey & Hawkes survived his demanding cliency by far the longest, thanks largely to the business acumen of Ralph Hawkes and the firm, musically-informed sympathy of Ernst Roth. In the forties Hawkes negotiated the purchase of the catalogue of the old Edition Russe, which brought with it many of Stravinsky’s greatest earlier works, including Petrushka and The Rite, and masterpieces of the twenties and thirties like the Piano Concerto, Oedipus Rex, and the Symphony of Psalms. So the Boosey & Hawkes catalogue provides a comprehensive survey of Stravinsky’s music, in all its diversity.

Stephen Walsh, 1996

(Reader in Music at the University of Wales, Cardiff; writer and broadcaster on music and biographer of Stravinsky.)