Birtwistle: interview explores new opera The Minotaur

Birtwistle: interview explores new opera The Minotaur

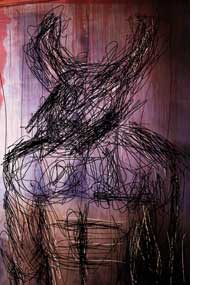

Harrison Birtwistle discusses his new opera which takes the stage at Covent Garden in April.

What first attracted you towards the Minotaur myth?

It was just part of a bundle of myths that interested me and, initially, it didn’t necessarily stand out as a story suitable for operatic treatment. The arrival of a scenario by Friedrich Dürrenmatt prompted renewed interest but the essential problem remained the Minotaur himself. He is half-man and half animal, so what does this mean dramatically? Like a lot of projects I needed a way in, and this came in discussions with the poet David Harsent, who suggested separating the two aspects, rather like Jekyll and Hyde. When the Minotaur dreams, he dreams as a man and questions his whole existence.

This is your second opera with David Harsent as librettist, following Gawain. What draws you to his work?

We understand each other. I discovered he’d written a sequence of poems called Mr Punch, and then I found we shared similar poetic interests. He is particularly good at creating landscapes, and the language that those landscapes demand. That is very important to me. I’ve never needed to request things in advance as he knows what I find interesting. It’s only when I’m composing the piece that I might need to request changes. Then I usually ask him to go deeper, to go darker, or to expand the moment.

How did you develop the characters of the opera?

The good thing about myth is that the basic storyline is known by the audience, so you can do things with it. But the characters are not known as real human beings – the danger is that they can just inhabit an invented narrative. So we looked for ways into the myth to make it work for the stage, for instance by having the dreaming Minotaur speak to his mirror image. All three main characters, the Minotaur, Ariadne and Theseus, are caged and looking for an escape route from their predicaments. For Theseus the answer is the ball of twine, but where does it come from? It is not as if Ariadne just buys it from a shop. So in the opera the twine is provided by the Oracle as a solution to her questions. These are the sorts of things we worked on.

The idea of a labyrinth has been central to many of your works. Did all paths lead to the new opera?

The importance of the labyrinth in my music is really a personal compositional matter, so the fact that a maze is central to this story is largely co-incidental. As in many of my recent pieces I’ve tried to create a single continuous line running like a thread. Sometimes it’s a melody, sometimes it’s proliferated into harmony, or it may be silenced for dramatic reasons and then resume.

How does the path through the opera relate to the nature of time?

There is a linear narrative in the sense that you can enter the maze and later come out of the same door, but your route can be different each time and this is important dramatically. There are three ritual labyrinth sequences in the opera: in the first a single Athenian ‘innocent’ is ravished and gored by the Minotaur, in the second the remaining group is slaughtered, and in the third Theseus slays the Minotaur. At the end of the first and second sequences the Minotaur sleeps and dreams, whereas at the end of the third he awakes fully as a human, only to find eternal sleep. I’ve also inserted three Toccatas of ‘composed silence’ in which time stops, allowing the drama to have the space just to tick over.

Do you have particular stage pictures in your mind?

The starting point was the image of a beach, with Ariadne walking ‘this shoreline like a flightless bird’ when she sees the sails of Theseus’s ship and a means of escape. But beyond that the stage is really an open psychological space for the director. Even when the ‘innocents’ enter the maze, Ariadne and the chorus are somehow present too, observing and participating in the ritual sacrifice. Imagining John Tomlinson on stage in the lead role was integral to the whole project and I fully intended it to be a vehicle for him. I’ve heard him sing in Punch and Judy and Gawain and I modelled the vocal range on that of Hagen, one of his greatest Wagner roles.

The vocal part of the Minotaur involves much more than singing.

Yes. In his bull-state he seems to roar incoherently as he strives to communicate, drawing the victims towards the centre of the labyrinth, whereas in his dream sequences he sings conventionally. When Theseus confronts him the Minotaur moves from his animal to his human state. He recovers the powers of speech fully at the moment of recognition, but his language disintegrates as he dies.

Your vocal writing seems less angular in recent stageworks. Is this a practical or a musical development?

Both. I’ve moved towards a more consonant style of writing for the voice to make the lines sound more natural and to help the text come over. In compositional terms I’ve lessened the overlapping of the pitch layers. There are still dramatic highs and lows for each line but generally the voice occupies a narrower, more comfortable, space within the spectrum.

How do the various choral groups function in the opera?

The main chorus is referred to as The Crowd and they are fickle like at a football game. They can be insulting and goading the Minotaur to acts of violence at one moment, or singing a lament over the victims or the dying Minotaur at the next. Then there are smaller choral groups, like the ‘innocents’ or the vulture-like Keres headed by solo voices. In this opera I see all the choral singers as physical characters on stage, rather than functioning as a backcloth.

Having completed another opera, how do you view the genre?

My view hasn’t changed. I’m still most interested in intimate drama. The challenge with the machinery of a large opera house is how to still allow the small-scale human details to come through.

Interview with David Allenby

View a video podcast of David Harsent introducing the opera.

The Minotaur (2005-07 )

(world premiere)

Opera in 13 scenes

Libretto by David Harsent

Commissioned by The Royal Opera

Antonio Pappano Conductor

Stephen Langridge Director

Alison Chitty Designer

The Minotaur: John Tomlinson

Ariadne: Christine Rice

Theseus: Johan Reuter

Snake Priestess: Andrew Watts

Royal Opera, Covent Garden

15/19/21/25/30 April, 3 May 2008

The Royal Opera, Covent Garden, London

www.roh.org.uk

> Más información sobre la obra: The Minotaur

Image by permission of Simon Harsent