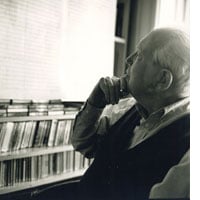

In Conversation with John Link, Elliott Carter Scholar

William Paterson University professor and internationally renowned scholar John Link talks with Boosey & Hawkes about the legacy and music of Elliott Carter and the supporting efforts of the Amphion Foundation.

What is the mission of the Amphion Foundation? Why was it established?

The Amphion Foundation was established by Helen and Elliott Carter in 1987 to encourage the performance of contemporary concert music, particularly by American composers. The Foundation’s grant program provides support for a wide variety of performing and presenting organizations, from small groups with tiny budgets to some of the biggest arts organizations in the country. Since Elliott Carter’s passing in 2012 the Amphion Foundation also has taken on the responsibility of promoting the legacy of his life and music. We have created a website for all things Carter (www.elliottcarter.com), and Elliott is now on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/chronometros) and Twitter (@Chronometros) as well. The Foundation also has its own website: www.amphionfoundation.org.

How has Elliott Carter’s music shaped today’s musical landscape?

For composers today Carter’s influence is unavoidable. The variety and vitality of his music, and the skill and wit with which he makes highly contrasting textures dance together in counterpoint, have inspired four generations of composers—from Pierre Boulez to Sean Shepherd. And his lifelong devotion to the idea that contemporary music can speak to the human condition as powerfully and meaningfully as literature or theatre or dance or cinema or the visual arts makes him a role model for all musicians today.

Elliott Carter became extremely prolific in his later years. What caused this explosion of creativity?

Getting older for one thing! As a younger composer he wrote very slowly, and I think that began to bother him more and more. He worked very hard to streamline his compositional process, to figure out the most efficient ways to realize his musical ideas. He developed a simplified harmonic language that was not only easier to work with but also more versatile, and he pared down the contrapuntal density of his textures. Both of those changes had a very positive effect on his music. They not only made it easier to compose and perform, they also broadened its expressive range. And of course he was blessed with a musical imagination that just never quit!

What qualities exist in this later music that do not exist in his earlier works?

Carter’s commitment to writing music that reflects human experience never wavered. He always chose projects that challenged him in new ways, but he also took an incredibly broad view of his life’s work, so those projects always developed and extended discoveries he’d made in his previous pieces, both technically and expressively. The fruits of those labors in the later music are greater clarity, and a much richer and more vivid representation of the different ways people interact with each other and experience their lives. Those qualities help to explain why his later pieces are now among the most popular with audiences.

What conclusions have you drawn about Carter’s musical voice? Would you say his style was still evolving up until his last work?

Absolutely! One of the unfortunately enduring myths about Carter is that he settled on a kind of abstruse and uncompromising Modernism in the 1950s and never budged thereafter! In fact he paid close attention to what was happening in the world, and in contemporary music, and he adapted to changing tastes and circumstances with enthusiasm, grace, and good humor throughout his long career. What he didn’t compromise was his belief in how much contemporary music can tell us about our lives and our experiences.

The composer’s final work, Epigrams for piano trio, required extensive discussion and editorial work due to Carter’s not being able to review the final proofs before engraving as his health was failing in late 2012. What challenges did you and the editorial team at Boosey & Hawkes come across in engraving this work?

We are very lucky that Epigrams was essentially complete before Elliott’s health began to decline. It’s a marvelous and remarkably ambitious piece that turns the disabilities of old age into opportunities for playfulness and wit. It’s unfortunate that Elliott was not able to review the proofs, which were left with a variety of small errors and inconsistencies of the type that inevitably arise as a score is prepared for publication. But the many people who were involved in the editorial process—including David Nadal, who engraved the score—worked very hard to arrive at the best possible resolution of the uncertainties that remained, most of which were minor.

What does the future of Elliott Carter scholarship look like?

This is a very exciting time for Carter scholarship. Interest in Carter’s music is burgeoning, particularly among younger scholars. I’m pleased to say that the Amphion Foundation is sponsoring a new journal, Elliott Carter Studies Online (www.carterstudies.org) and our first issue will be appearing early in 2016. Although sadly there won’t be any more new Carter pieces, the astonishing bounty of music he composed during his last two decades—and its relationship to his earlier work and that of his contemporaries and predecessors—is only beginning to be studied. And many of those pieces are only now being heard in concert halls and on recordings for the first time. As more and more people get to hear this remarkable music for themselves it will no doubt inspire, not only scholars, but also singers, conductors, instrumentalists, orchestras and opera companies, and music lovers around the world.

Interview conducted by Patrick Gullo

For more information about Elliott Carter, click here.

View this news story in Spanish.

Photo: Meredith Heuer