Revised Standard Version of The Bible (E); the Vulgate (L); Stabat Mater (L) with additional text by the composer (E)

1 baritone solo, small chorus(="narrator chorus", 8-24 singers of professional standard), larger chorus (professional chorus minimum 80 voices, amateur chorus minimum 120 voices)

2(II=picc).2(II=corA).2(II=bcl).1.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):t.bells/tuned gongs/tgl/Sanctus bells/5tpl.bl/SD/BD/susp.cym/sizzle cym/tam-t-chamber organ-strings

Abbreviations (PDF)

Boosey & Hawkes

After writing my Seven Last Words from the Cross in 1993, I always knew that the inevitable next step would be a setting of one of the Gospel Passion narratives. It has since been my ambition to tackle such a project. I decided on St John's text, as it is the version with which I am most intimately acquainted, hearing it recited or sung every Good Friday in the Catholic liturgy. In fact, since my student days in Edinburgh I have regularly participated in the Gregorian or Dominican chanting of the Crucifixion story on that day. This simple music has had an overriding influence on the shape and character of my own Passion setting.

The scoring is for one principal soloist, Christus - a baritone, a chamber choir which carries the Narrator's words, a large chorus which takes all the other text, including the characterisation of the other main players in the drama, and orchestra. The instrumental approach was to make a sparse and lean texture, (so there is limited percussion, no harps or the usual keyboards, although there is a chamber organ), while maintaining the potential for full dramatic climaxes where necessary.

I have divided the work into ten movements. At the end of movements 1-9, I have interpolated a Latin text which takes something of the general theme and development of the story, and allows time for a more objective and detached reflection. The final movement is purely instrumental - a song without words.

I have a love of liturgical music, and specifically, of the cool purity of chant. As well as this, I love opera, and the composition of this Passion has come immediately after my new piece for Welsh National Opera, The Sacrifice. I was aware of the inevitable effect that this piece was having on the progress of my St John narrative. In fact some of the opera music has drifted quite naturally into the new sphere. I was also aware of the paradoxical tension created between the two highly contrasted musical contexts - liturgical chant and music drama. Balancing, creating opposition sometimes, and at other times elisions and cross-fertilisations between the two, became the delight in composing this work.

My St John Passion is dedicated to Sir Colin Davis in his 80th birthday year, as a token of my admiration and appreciation for one of this country's greatest musicians, and for the wonderful music making he has given us throughout his life.

© James MacMillan 2008

Reproduction Rights

This programme note may be reproduced free of charge in concert programmes with a credit to the composer

Choral level of difficulty: Level 5 (5 greatest)

This work is a major achievement and as fundamental an addition to the choral repertory as, say, Britten’s War Requiem. It was written for Sir Colin Davis’ 80th birthday. To follow in Bach’s footsteps in creating a work which shares a title with one of his great works rather than calling it something new and trendy shows another aspect of the fundamental nature of this work. It is huge, lasting nearly an hour and half. Its forces are modest on one level – only one soloist, Christus, a baritone. He needs to be a force to be reckoned with and have real staying power up on top G flats. A ‘narrator’ chorus (SATB) takes the role of the Evangelist. This is a refreshing and original change to our perception of this role. However, such is the nature of the writing for this group that a small professional ensemble is probably needed both for security and projection. In practical terms this, then, balances the economic benefit of having only one professional solo role. The ‘large’ choir takes the other ‘personality’ roles such as Pilate and Peter, and of course takes the role of the turbae – the crowd. This group needs to be sizeable as the orchestra is large and is used fully. There are many fortissimo passages in this work. It is a dramatic story and is dealt with as such.

This Passion would stretch many amateur choral societies. The writing is dense and complex in places, the rhythmic interaction between choir and orchestra often difficult, and tuning could be a real issue in those (absolutely beautiful) passages which MacMillan leaves unaccompanied for several minutes before bringing the orchestra back in again (movements three and four). Anyone who has sung Bruckner’s E minor Mass will recognise the issue. The choir’s sopranos are also asked to hum top B flats pianissimo amongst other effects. There is a sizeable passage of cluster singing which will challenge some choirs. One could go on listing such things, but the point is made. This is a work for professionals or for amateur choirs used to working at professional standards – the symphonic chorus with a generous rehearsal schedule. It should be taken up as a ‘standard’ by the Three Choirs Festival and similar choral focused organisations. It would be impossible to mount a performance of this Passion safely with a normal ‘on the day’ three-hour rehearsal, so many singers may experience this important work in the audience rather than on the platform.

The originality of the St John Passion lies in MacMillan’s ability to mix old with new, rather in the manner of Bach in his day. There are passages of sumptuous polyphony, there is a new look at the text where passages of Latin are interspersed with the Gospel story in English. After Peter’s denials MacMillan inspirationally gives the choir the Latin text Tu es Petrus to sing, redeeming Peter with Jesus’ words of affirmation rather than having him break down into tears. Later, in movement seven (Jesus and his Mother), MacMillan introduces not only part of the Stabat Mater but also his own words in the manner of a Christmas carol Lully, lulla, my dear darling. At the end of the work, in the final movement which is purely orchestral, a kind of via doloroso march, he introduces a Scots lament over quite brass chords. The string writing here, and especially the elegiac 'cello lines are deeply reminiscent of the early 20th English school. These points stick out as personal markers in a work which deserves world-wide performance. This should be the War Requiem of the 21st century.

Repertoire note by Paul Spicer

"MacMillan has come up with a masterly work that has all the hallmarks of a 21st-century classic… MacMillan is a master of ratcheting up the tension, building the drama, his subtle use of syncopation adding to the effect. But he can also turn his hand to the most lyrical, vulnerable music."

Musical America

“A blazing blockbuster, a piece as fiercely communicative as anything that the 48-year-old MacMillan has written before…. The end of Part One was masterly: no loudspeaker wailing as the Crucifixion loomed, but a resigned, pianissimo meditation, threaded with keening instrumental solos.” The Times

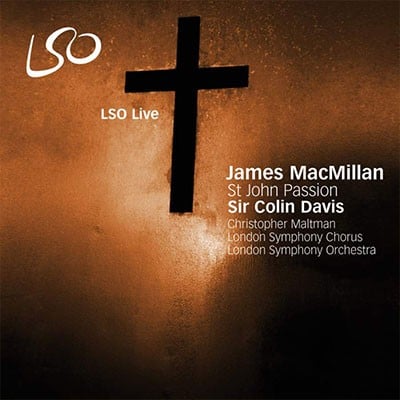

Christopher Maltman / London Symphony Chorus /

London Symphony Orchestra / Sir Colin Davis

LSO0671