Britten’s War Requiem in Hiroshima - Roderick Williams Performer Diary

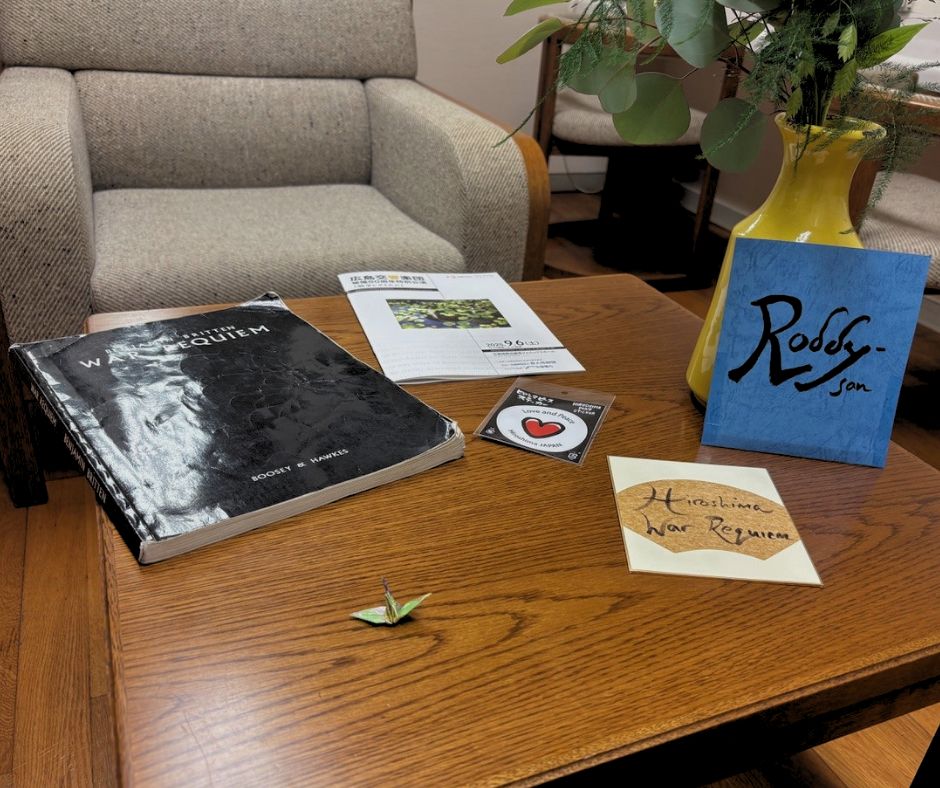

We follow baritone soloist Roderick Williams as he reflects on his experience performing Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem in Hiroshima’s Peace Park, observing 80 years since the atomic bombing of the city.

Phoenix Hall in Hiroshima’s Peace Park plays host to a uniquely poignant performance of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem on 6 September 2025, observing 80 years since the atomic bombing of the city. Japanese and British performers combine for the event, with soloists Hiromi Omura, James Gilchrist and Roderick Williams, the Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra, the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus and the NHK Hiroshima Children’s Chorus, conducted by Gavin Carr.

In a series of diary entries, we follow baritone soloist Roderick Williams as he reflects on his experience performing this powerful work in Hiroshima.

02 September 2025: Arriving in Hiroshima

After more than 15 hours in the air yesterday we have arrived here in Hiroshima. The choir has gone straight into rehearsal today while James Gilchrist and I have had the day free for our voices to recover from the journey, and for our brains gently to unscramble.

It is in the nature of being a freelance musician that one goes from project to project and so I can only really look forward to something in my diary in general terms. I must focus as much as possible on the project in hand. This event has been in my diary for a while and I have been looking forward to it, but I have not had much brain space to imagine in advance what it is going to be like.

Now that I’m here, a number of things are occurring to me. First of all, I have come to understand how much this project has meant to its instigator, conductor Gavin Carr. This has been a dream of his to achieve here in Hiroshima for decades. It has also been a huge undertaking to manage the logistics for 160 choir members to travel to Japan. The team at Specialised Travel agents under Tony Hastings have been working on it for at least four years. I have arrived therefore somewhat at the tail end of all this preparation and I’m coming to understand just how much has been invested in it from so many people.

In talking to various choir members during the travelling, I have come to realise just how excited people have been at the prospect of singing this piece in this city in this anniversary year. I am told that singers have come from all over the UK, not just from Bournemouth, and from further afield - Germany, the United States and even one chorister from Japan. Their sense of excitement has been inspiring and has given the project a sense of occasion that I hadn’t especially felt before arriving.

I am also delighted to meet our soprano soloist Hiromi who has travelled not from Japan but from her home in the Auvergne via Paris to be with us. She has never been to Hiroshima before nor has she sung this piece and so I’m interested to see this work through her eyes.

Nor has the Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra played the music before. I am told that early rehearsals have been spectacularly good, the result clearly of much preparation. I am also told that the concert is a complete sell out which makes the occasion even more of an event. I have to admit I wasn’t sure how the Japanese audience would respond to this piece with its combination of Latin text and very particular English poetry. However, their sense of curiosity has certainly been expressed at the box office.

So far, I seem to be defeating jet lag and I’m looking forward to my first rehearsal with the orchestra tomorrow afternoon.

03 September: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the first rehearsal

Today began with a visit to the Peace Memorial Museum and the Peace Memorial Park in central Hiroshima, followed by my first rehearsal with the chamber orchestra in the afternoon.

We were guided around the gardens before visiting the museum and I found our guide’s understated, matter-of-fact presentation sobering. Many of the images inside the museum were pretty graphic and the mood inside was very sombre, despite the large number of tourists moving through. I was struck that there was no mood music piped inside the museum, which meant that Britten’s score was resounding inside my head as I made my tour.

During the afternoon rehearsal, these images came to mind sometimes unexpectedly. I found, for example, that the poem that begins “After the last blast of lightning in the East” caught me by surprise. I found myself unable to continue singing twice in a row, before I was able to gather myself and continue the rehearsal.

However, I was also struck by the different circumstances of the conflicts Britten and Wilfred Owen were describing, and the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima. For one thing the poem in Strange Meeting describes a battlefield with two combatants meeting after death. Here in Hiroshima, I’m very much aware that this city was no battlefield. The American air crew had no contact with the people on whom they dropped the bomb. In fact, their journey was made with comparative ease. The people on the ground, however, were caught in the middle of their daily life, and the change from that city morning to a scene of total devastation was instant. In that respect the conflict described in Britten’s War Requiem is very different.

The playing of the Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra is outstanding. The musicians have clearly prepared immaculately ahead of time, and this challenging score holds no fear for them. Rehearsing with Gavin and James yesterday was an absolute pleasure.

Gavin tells me he has in the past sung the baritone solo all over the world and I am struck that the piece has had much more impact globally than I had previously thought. I am much intrigued to see how this piece goes down here in Hiroshima on Saturday.

04 September: Benjamin Britten's music in Japan

Today we had our first rehearsal in the actual venue right next door to the Peace Memorial Museum. During the morning James Gilchrist, my wife Miranda, and I made a visit to the elementary school just round the corner from our hotel, which was one of the few buildings that miraculously managed to survive the atomic bomb blast. The school became an emergency refuge soon after the devastation, and there are still inscriptions on the walls from people trying to find or leave news about family members and their whereabouts. It’s extraordinary to think that anybody could have survived the blast but, again miraculously, three children did survive who happened to be changing their shoes in the school’s basement. Their stories and the stories of other survivors have been both harrowing and inspiring.

In the afternoon, we rehearsed with the orchestra in the venue. I was struck how several moments, not just the final ‘gamelan’ chorus of resolution, but other moments in the score sound oriental, perhaps even Japanese. One such moment is the bassoon solo in the Abraham and Isaac section. Gavin was asking the marvellous bassoon player to give the solo as much character as possible and it called to my mind images of kabuki theatre characters. The old man is a stock character and I think Britten captures this perfectly. It could be the soundtrack to a black-and-white Japanese film or live theatre.

In a later poem, Wilfred Owen personifies Age as a white haired old man and the Earth as a sorrowful, exhausted woman. This brought to mind again images from Japanese theatre and I found online pictures of masks used in Japanese Noh theatre.

I know that Benjamin Britten was intrigued by the music of the Far East and was even commissioned by Japanese orchestras, but it begins to occur to me as I listen to the music here in Japan just how Japanese some sections sound.

05 September: Miyajima Island and final musical preparations

Often a place or setting really colours the way I hear music. For example, I remember attending a performance of Mahler‘s Symphony No. 1 in Tel Aviv, played by the Israel Philharmonic. Especially when the clarinets were playing, with their natural affinity for klezmer style, it struck me how much the music sounded Jewish. When I heard the same piece played by the Vienna Philharmonic not long afterwards, it now seemed to me that the symphony was only full of Austrian waltzes and Ländler.

So, it is that hearing the War Requiem played and sung here in Hiroshima, the music sounds peculiarly like its surroundings.

James, my wife and I spent this morning on a visit to Miyajima Island, a popular tourist destination, to see the famous floating shrine. Our visit included another shrine halfway up a hill. Near the top of the steps to the shrine there was a large bell that is rung by a length of wood attached to a pull-rope. Visitors are invited to ring the bell just once and make a prayer. The morning was punctuated by random rings of this solemn prayer bell.

And so it was that, during our afternoon rehearsal (the first time that the full orchestra, soloists and choir came together) I found myself drawing parallels with what I know or imagine of Japanese music and culture (which, I’m sorry to say, is not especially much). I suppose I have experienced the War Requiem before in the context of English church music, with its premiere at Coventry Cathedral. But now I listen to the solemn bell that begins the whole Requiem as the Japanese audience might hear it tomorrow. It is surely a gesture that they will recognise.

At the top of the steps of the Miyajima shrine, there is a small Buddha figure sitting on top of a wooden box. You drop your coins in through a hole at the top of his head and they fall through to the coffer, striking tiny bells as they go. These bells are all on the same tinkling pitch. I was reminded of this Buddha figure as I listened to the opening of the Sanctus, which Britten begins with a single pitch on the piano and percussion, starting softly and slowly, growing louder before the soprano soloist sings triumphantly. I have equated this before with the Sanctus bells in Catholic churches, but today I heard it in a different way again. I was picturing Japanese theatres and Buddhist temples.

When the Hosanna section erupts out of the Sanctus, and again at the end of the Benedictus, an image arose in my mind of rows of Japanese drummers pounding away at their huge drums, double-handed, and again I wondered whether this sound-image of thrilling ritual in Britten’s music would be something that tomorrow’s audience would find familiar.

In the evening, we had our dress rehearsal and this was the first time that all the forces were gathered together: soloists, chorus, orchestras and children’s chorus. The children are singing from the lower gallery, above and behind a lot of the audience. There are about 50 of them, boys and girls. When I hear this piece back home, often sung only by boys voices perhaps from a cathedral choir, it feels as though Britten is making a point: during the First World War, these boys’ innocence would be cut short in only a few years and they would soon be picking up rifles themselves to go and fight in Flanders.

Here in Hiroshima, the narrative is different. During the allied conventional bombing raids of Japan in 1945, the Japanese government was anxious that traditional Japanese wooden houses would be especially susceptible to fire bombing. To mitigate this, they organised teams to demolish rows of houses to create fire breaks. As the men were already fighting, and the women taking up the duties the men had left behind, the job of demolishing the houses fell to teams of school children aged between 11 and 17. On the morning of 6 August 1945, work had just begun on demolishing houses. The atomic bomb detonated at 8:15 am, and directly under its blast were thousands of school-age children at their duties. In the evening’s rehearsal, when I heard the children sing in such numbers, I heard the voices of those house demolition teams.

Today’s rehearsal was also the first time that James and I had heard our colleague, Hiromi, sing with the chorus. She is a lovely, humble, slender woman and yet she sings with the most extraordinary vocal power, perfect for this role. She is also a physical singer, her body moving naturally with the effort she makes. As I watched her she somehow conveyed great strength with immense vulnerability at the same time. She reminded me of the harrowing tales that I had read in the Peace Museum, of survivors of the blast crying for help, of mothers desperately searching for their children. Her singing of the Lacrimosa was almost unbearable to watch, so poignant was it. I dare not share this with her until after the performance.

This was also the first rehearsal at which the chamber orchestra heard the music of the full orchestra and chorus. Gavin had warned them previously that the climax of the Libera me would feel like the end of the world, and he repeated this warning at this afternoon’s rehearsal. He described the sheer physical power of the moment, sound passing through our bodies like waves, and told them that, when he first sang the piece as a baritone soloist himself, he in turn had been warned of this moment by the tenor soloist.

When we came to rehearse this movement, it occurred to me that the opening, as Britten first announces the Libera me theme so quietly in the bass and side drums, brings to mind what Hiroshima might have been like in the hours after the blast. In a strange way, for Hiroshima, this music is the wrong way round. It should start with the end of the world climax, and then descend into this eerie, creepy silence, full of menace and the smell of death.

I let all these thoughts swim in my head during the afternoon rehearsal and felt my emotions churn and battle. For the evening, however, I knew I had to keep my emotions in check. Gavin told the chorus beforehand that his singing teacher from early in his career, Galina Vishnevskaya, had said to him: “Gavin, to sing, you must have a hot heart but a cool head”. This is true, but for me to do my job in this performance I need to keep my heart cool as well otherwise it might explode. I used the evening run-through to practice keeping my cool.

At the end of the afternoon rehearsal, we had some speeches from Masao Senoo, Chairman of the Board of Hiroshima Symphony Association, and from surviving relatives of Benjamin Britten, including his grandnephew Bill, who is singing in the basses of the choir, and grandnieces Sophie and Tamara. We were able to express our thanks to the orchestra, to our major sponsor of this trip (who is also singing in the choir) and to everyone at Specialised Travel who had made it happen.

I found the speech from the Chairman of the Board, which he made in English, especially moving. He taught me something that has become evident in what I have seen around me here in this city in the past few days. Yes, of course the story is about 6 August 1945 and the dropping of the first atom bomb. But Hiroshima has another message, a stronger and more enduring one. It is a message of peace, not just for this city or for Japan, but for the world. The message is: if you love peace, then this is your Ground Zero. At a time when several world leaders seem to be revelling in their preparations for war, this message deserves to be heard ever more loudly.

06 September: The performance

And so we have arrived at the performance, the reason for our being here. The auditorium is packed and there is a sense of excitement backstage and front of house. In fact, I had arrived over an hour early in order to warm up and also recover from the intense heat and humidity in the city (it’s only a short walk to the Phoenix Hall from our hotel, but one can easily soak through a t-shirt in that time!) and when I arrived, many orchestral musicians were already on stage practising.

One aspect of being a soloist in this sort of concert is that I get to experience the piece from a seat right up front beside the conductor, in the jaws of the orchestra, sitting still and looking out at the audience. When I’m not actually standing to sing, I sit almost invisible and it’s an amazing vantage point to look out and observe people. I study the audience as the evening unfolds and wonder what they are thinking.

Many are following the translation in their programmes, especially when James and I get up to sing to them in English. There’s far less repetition of course when we sing the Wilfred Owen poetry, compared with the Latin text of the chorus. Others are happy to watch the event unfold as it happens. I have no idea how many people are familiar with the piece or the composer. I’m inclined to think almost no one, but that is to make quite an assumption.

I notice a gentleman in the front row at my feet who listens to the whole concert with his eyes firmly closed. I wonder if he is asleep but he opens his eyes very quickly during the gaps in the music if the choir stands or sits as he checks what is going on. Not even the climax of the Libera me can persuade him to look up. A woman far out in the stalls to my left spends the second half of the concert with a hand over her mouth as though frozen in horror. Perhaps she’s actually just trying to suppress a cough! But it looks as though she cannot believe what she is witnessing.

The audience as a whole is attentive, still, calm, patient. I might project all sorts of emotions onto them but in the end I can’t tell what people are thinking.

I manage to keep my head and heart cool and am thus able to deliver my lines, especially the conclusion of Strange Meeting, without my voice quavering. I hope this allows others to be moved.

And when the last notes die away and the music is over, there is a long, long silence. Gavin holds the moment and I try to imagine what is going through his mind right then. Years of work, his decades-long dream, is finally realised and all his concentration focused into this piece is now complete. I daren’t look him in the eye: one or other of us is bound to have a wobble!

Some audiences around the world leap to a standing, cheering ovation no matter how a performance has gone. Others will be more reserved. London audiences can sometimes get to their feet almost before the final chord has sounded, but that’s because they need to run for a train. Here in Hiroshima, they gave what I’d describe as warm applause while remaining seated. It was a generous response; no whooping or whistling, no standing. Respectful.

But the applause went on and on. We came back onstage several times. At one point, Gavin gestured to each section of the orchestra in turn for them to stand and receive recognition: percussion, brass, horns, woodwind. Each of the string sections had their moment, second and first violins separately. It looked a bit like The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra. And still on went the applause.

We came off stage again… and then went back on. What I had thought was warm applause had turned into something more insistent. I could hear the applause continue long after the orchestra had left the stage. As the choir eventually began to file out, back rows first, choristers in the front row told me they were applauded by the remaining audience all the way to the end.

It’s a little difficult genuinely to gauge reaction from another culture in another language, but all the orchestral members I spoke to afterwards were grateful for our being there and for the project. In the end, it often comes down to individual anecdotes described by members of the chorus or our family and friends who had been listening in the audience. One chorister told me they had been approached by someone who told them that, as a follower of the orchestra for some time, it had been the best concert he had ever been to. Obviously we like to hear such things and hope that this concert will have resonated deeply with those who were there. It may take some time to assess just what impact the War Requiem made on them.

Photo: Tamara Britten, Sophie Blake (née Britten), James Gilchrist, Bill Britten, Heather Carr, Gain Carr, Hiromi Omura, Roderick Williams.

It certainly made an impact on us. We were euphoric afterwards as we left the concert hall and later as the chorus and soloists gathered at our hotel for our final meal together. Over some excellent food and with plenty to drink, we swapped stories and experiences, took photos and prepared to say farewell. I was seated at a table which included the grandnephew and grandnieces of Britten who had made the journey to be part of this occasion: Bill, singing with the basses, and sisters Tamara Britten and Sophie Blake who had sat in the audience. Gavin paid special and moving tribute to them.

Gavin’s terrific speeches thanked everyone who had worked so extraordinarily hard to bring his dream to fruition, including The Specialised Travel team who had arranged the journey, Tony Hastings and his wife Annie who led that work, Steve Brosnan who had sponsored the tour so generously (and sung in the tenor section) and everyone from the Bournemouth Chorus and all the guest singers. It’s not often I have seen a room of (mainly) British people get to their feet - multiple times - to applaud and acknowledge each other but the speeches were so eloquently expressed and the sentiments so heart-felt that we could not help but mark the moment.

Amongst many wonderful and kind things Gavin said, one struck me especially. He wondered aloud whether, on the hundredth anniversary of the atomic bomb explosion, and on subsequent anniversaries of note, this piece might ever be performed in Hiroshima again, that it might gain its place in this city of Peace. Who knows. But he reminded us that we were here at this first performance and he felt that we had done it justice.

Before my part in this project began, I had to consider that our enterprise could be viewed by some as an extravagant holiday gesture made by a party of well-intentioned but ultimately patronising tourists. For whom exactly might this feel like an act of reconciliation, people might ask? Why use this piece, so steeped in an English experience of battle-field war and its resulting poetry? What were the Japanese audience supposed to take away from this?

I can’t answer for the Japanese; I hope in time I will hear more of their response to the concert. I can only speak for myself. I feel I have learned something. I have discovered more about the universality of music as I have listened to Britten’s music through a Japanese lens (well, Japanese as I perceive it, perhaps), and have come to understand the nature of Britten’s fascination with the music of the Far East. I have learned so much more of the history of the event of 6 August 1945 and its aftermath, its significance in world events at the time and ever since. I have come to understand the nature of our desire for peace, our need to commemorate and to retell the stories in order to improve humanity’s co-existence and do everything we can to prevent history from repeating itself.

I have always found performances of the War Requiem intense, without fail. It would seem that its message is always apposite, always timely, such is our seemingly endless thirst for violence and conflict. Today in 2025 the menacing dark clouds seem to be gathering with ever more threat. To all those who bristle with so-called patriotic, nationalist vigour and seek to defend their position by the taking up of arms, I would say, there is a piece of music I’d really like you to hear.

10 September: Back home

I am now back home in the UK and have launched straight into the next project, no time for jet lag. Talking with my colleagues here and describing my experiences in Japan to them, they reminded me that Britten most definitely included Japan on his tour to the Far East in 1956, and it was there that he saw the Noh play Sumidagawa that impressed him so much, he went twice. His experience of this play in particular was the basis of his first church parable, Curlew River and so of course it is no accident that Far Eastern musical influences and cultural aesthetics pervade his style after 1956 right up until the end of his life. I guess I just hadn’t appreciated this influence within the War Requiem until I heard it in Hiroshima.

Being part of a performance outside the UK does cause me to look at familiar music in a different light. Earlier in the year I sang the War Requiem in Miami, and this autumn I am due to sing it in St Louis. No doubt the experience is tempered by the different cultural context and world events. We shall see.

I am hugely glad to have been included in this trip to Hiroshima as I relish any circumstances that give me cause to listen with fresh ears. I look forward to joining the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus and Orchestra next year for Tippett’s A Child of our Time.

Roderick Williams, 2025

> Find out more about the concert

> Find out more about Benjamin Britten: War Requiem

Header Headshot Photograph by Theo Williams. Diary Photographs by Roderick Williams.