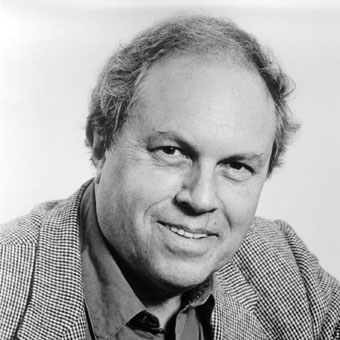

Jacob Druckman

An introduction to Druckman’s music

by Mark Swed

At the heart of the works of Jacob Druckman lies the bold, sure, and often arrestingly physical dramatic gesture. Over its 40-year span, his music has progressed through several styles, from the earliest published scores such as the neo-Classical Divertimento of 1950, and the 1960s experimental pieces for electronics and live instruments, to the lavishly colored orchestral tapestries of the 1970s. It is a body of music created for a wide variety of media – instrumental, electronic, and vocal – and it is a music that has ranged from the purely abstract to the explicitly theatrical.

Druckman’s unfailing sense of the striking impact and presence of sound is evident from the earliest pieces, with their rhythmic exuberance and searing melodic climaxes that seem to draw on the young composer’s experience as a violinist, conductor, and jazz trumpeter. But as his instrumental and vocal writing became more sophisticated, Druckman found increasingly inventive resources to express intense and complex dramatic situations. In works like those in the Animus series, the drama becomes a visceral experience through the exploration of such elemental human concerns as madness, violence, and sexuality. In one extreme example, the highly virtuosic, ironically titled Valentine for solo contrabass, Druckman requires the soloist to assault his instrument with near sadistic ferocity.

Yet Druckman’s scores have always exhibited another characteristic as well: that of careful structure, built with meticulous attention to detail. The process of integrating these two sides of his character – the passionately physical expression with the cooler intellectual organization of pitches and rhythms – has been a consistent factor throughout the composer’s development.

Such Classical and Romantic aspects of his music – Druckman has described them as Apollonian and Dionysian – have come into direct opposition in some of his most recent work through the building of structures upon musical reference. Typically he has used musical quotation in highly dramatic ways. In Delizie contente che l'alme beate (1976), for wind quintet and tape, wisps of an aria from Cavalli’s opera Il Giasone float eerily through the score; while in Aureole (1979), Druckman honors Leonard Bernstein through a glowing construction built upon the pitches of the 'Kaddish' tune from Bernstein’s Third Symphony.

An example of the integration of all sides of Druckman’s musical personality can be found in his most frequently performed orchestral piece, Prism (1980), in which the three movements are based respectively upon quotes from three Medea operas by Charpentier, Cavalli, and Cherubini. In each movement of Prism Druckman reacts differently to the earlier Medea music, whether by trying to coax it gently into the 20th century or to fracture it aggressively. Consequently the drama here is on many levels: at times musical centuries seem in direct conflict, at others the conflict appears to derive from operatic connotations. But always, Druckman exploits fully the potential of his rich orchestral palette to create a magnificently changing sonic landscape that draws the listener into a world at once exotic yet with the relevance and immediacy of our own troubled times.

Mark Swed, 1996

(Chief critic of The Los Angeles Times)