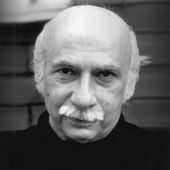

Giya Kancheli

The Finite Quality of Silence

The Music of the Georgian Composer Giya Kancheli

In addition to numerous polite references to the fact that music is capable of forging links between different nations, Beiträge zur Musikkultur in der Sowjet-union und in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, which was edited by Givi Ordzhonikidze and Carl Dahlhaus, contains an interesting remark about the significance of l’art pour l’art in music. “If a composer decides to adopt the slogan ‘art for the sake of art’ and makes a point of turning his back on real life, this does not mean that he is subscribing to the principle of ‘creative freedom’. Rather, he is subscribing to a strict law which has to be obeyed just as much as that of the opposite theory, which believes that there is a close connection between art and reality.” Such phrases were part of the defence strategy of those who refused to comply with the aesthetic demands of socialist realism, and were part of the gamut of rhetorical skills which every artist in the Soviet Union had at his fingertips. Messages such as these were transmitted in a cloud of ideological verbiage to those who knew how to decipher the code.

The Georgian composer Giya Kancheli was one of the many artists who were unable to reveal their views on art and what they really believed in. In fact he first became famous as the Soviet Union was on the point of disintegrating, and with it the hegemonic structures which made it difficult for artists from the non-Russian republics to survive in what might be defined as Russian Orthodox cultural life. Thus Arvo Pärt, Giya Kancheli, Alfred Schnittke, and Sofia Gubaidulina, who all lived for a time in the West or were forced to emigrate, constitute an avantgarde in two senses of the word: through the very nature of their works, and as forerunners of artists who, no longer under the control of the state, are hoping to receive the recognition they deserve.

A scholarship enabled Kancheli to live for a time in Berlin. He later moved to Antwerp, where he was composer in residence. He used to write a great deal of film music, like Arvo Pärt, Erkki-Sven Tüür and many other composers in the Soviet Union. It was one way of surviving as a composer, for work on the soundtracks was not scrutinized by the State Commissar for Aesthetics. Conversely, composers had to accept the fact that the scores were, so to speak, cut up like sausages and turned into juicy morsels which gave little idea of the original design. But at least it sharpened their feeling for drama, for cogent utterance and telling characterization.

All this comes to mind when we listen to Giya Kancheli’s impressive output, which includes seven symphonies, concertos for various instruments, an opera, and numerous chamber music works. In fact, there is something very natural about his musical world; it is as if the notes did not take their bearings from the laws governing polyphony, harmony, sequences and alteration, but from more general principles such as the duration of breath, pauses, crescendos and tension, excitement and calm, rising and falling. It is expressive music whose organic nature can certainly be understood without a knowledge of compositional terminology.

Kancheli’s instrumental writing has a kind of vocal quality that Julia Evdokimova has described thus: “As the music unfolds, the ‘thread’ of the argument becomes clearly discernible, and this has a special dramatic significance. It consists of a group of would-be voices which, like a festive choir, sometimes reaches us from a distance as if through the walls of a cathedral, and sometimes comes close to us, and attains to full and lavish polyphony.”

Those who are familiar with Kancheli’s music, and especially with his symphonies, soon become aware of the fact that, despite the difference in formal design, his pieces have many features in common: the tendency to dwell on short motifs that revolve around a certain interval (often a second); brusque orchestral outbursts set in a broad melodic stream; luminous wind passages; adherence to tonality; and an inquisitive approach to sound for its own sake. Kancheli does not employ quotations. Rather, his form and sonorities, his musical manners and his images seem to be distantly related to the sounds of his homeland, a sphere to which it is impossible to return. Givi Ordzhonikidze has commented on this: “A formal element that derives genetically from Georgian folk music cannot return to its original context without destroying the ancient tradition”. This may be the reason why Kancheli’s pieces resound and echo in our hearts. They do not evoke genre paintings which are at odds with reality as we perceive it. And their aura is similar to the one described by an oriental poet many centuries ago: “Be as patient as the earth, sow what you have heard, and await the harvest from the seed.”

In the Soviet Union Kancheli’s music was apparently considered to be just as fascinating as Georgia itself. The country has always attracted Russian artists in a manner that resembles the German longing for Italy. In the words of Leo Tolstoy, it was the ‘land of fate and greatness, of adventure, and of shining souls’. It was also a country that refused to surrender its identity during the many centuries of foreign rule, something that has been described by another poet, the unfortunate Osip Mandelstam. In his essays Armenia and Georgia, or, to put it more precisely, the Caucasus, seem like the Promised Land. “Russian culture has never been able to force Georgia to adopt its values. Wine improves with age: that is its future. Culture is in a state of ferment: that is its youth. Preserve your art, the slender earthenware vessel lodged firmly in the ground!”

Such associations spring to mind because they are familiar, and because we simply ascribe them to a particular work. However, they also emanate from the sounds themselves; from the many unusual adjacent seconds and simple melodic motives which are tender reminiscences of Georgian folk music; from the ‘oriental’ equanimity of the unruffled melodic writing, which another composer, Alfred Schnittke, has described as ‘the rare gift of a floating sense of time’. The music unfolds as sound pure and simple, and in an unabashedly emotional manner. Kancheli’s rejection of virtuoso rhetoric and technical complexity makes us aware of what we have lost as a result of our all-pervading cynicism, our fear of religious belief, our comprehensive refusal to listen to certain kinds of music, and our neurotic habit of trying to discern the tendency of the material, which not infrequently is nothing more than the tendency that self-appointed critics happen to approve of. We have lost the ability to feel the strength of music which is constructed on the basis of tonality and the diatonic scale; the courage to embrace a musical and religious creed, and the respect for its compositional structures; and finally the patience to listen to music which is not based on the notion of development, creates associative motivic chains, and, in an even and contemplative manner, seems to have materialized without having been composed. In Giya Kancheli’s Morning Prayers chords accumulate over a static unison passage as if the tendency of the material was of no importance whatsoever. It is an effect which we come across again and again in the composer’s music. Sometimes in fact he simply seems to want to make us aware of the finite quality of silence.

Wolfgang Sandner