Libretto by W H Auden and Chester Kallman (E,Cz,F,G,I)

Major roles: lyrS,dramM,hT,Bar; minor roles: A,T,2B; chorus

2(II=picc).2(II=corA).2.2-2.2.0.0-timp.perc:offstage bell/cuckoo-hpd(or pft)-strings

Abbreviations (PDF)

Boosey & Hawkes

Stravinsky’s largest work, his only full-length work for the theatre, and his first major work in English. It also represents the culmination of his neoclassical years, after which he started to rethink his musical language. The idea was prompted by seeing an exhibition in Chicago in 1947 of a series of Hogarth prints and he instantly recognized their operatic potential. The depiction of the ironic progress of the spendthrift heir of a miser from wealth via debt to madness and death is, in essence, retained in the opera. Stravinsky’s Hollywood neighbour Aldous Huxley suggested he contact the English poet W.H. Auden, resident in New York, to write the scenario and libretto, which Auden did with the assistance of his lover and opera buff Chester Kalmann. The text wittily grafts onto Hogarth’s quest narrative aspects of, among other sources, Classical pastoral, the Faust legend, fairy tale, circus, the Bible and opera in many different manifestations. This is brilliantly matched by Stravinsky’s music, which takes as its source the whole of operatic history from Monteverdi to Verdi via Rossini and Donizetti and large doses of Mozart. Yet it is neither parody nor pastiche; rather, in remaking all of opera into this one new opera, Stravinsky and Auden create a fable appropriate to their modern world: its kaleidoscope of sources speaks of the dislocated, alienated times in which they lived … even if, in a marvellous take on the ending of Don Giovanni, the final epilogue tells us it’s really only a piece of theatre! The Rake’s Progress can be appreciated on many levels, which might explain why it is still one of only a handful of 20th-century operas never to have been out of the repertoire.

Repertoire note by Jonathan Cross

One inspiration for this "moral fable" in "Italian-Mozartian" style ("I will lace each aria into a tight corset") was Hogarth's series tracking the downfall of Tom Rakewell, who squanders his inheritance on women, gambling, and drink and dies in a madhouse. In Auden's much admired libretto, Tom is equipped with a sporadic moral conscience, as well as a satanic alter ego: Nick Shadow. As in Oedipus Rex, man is here a victim of implacable forces that control and crush him. But Anne Trulove, steadfast in devotion, rescues Tom's soul. The pervasive detachment of Stravinsky's score doubles the pathos of Anne's final lullaby.

Repertoire note by Joseph Horowitz

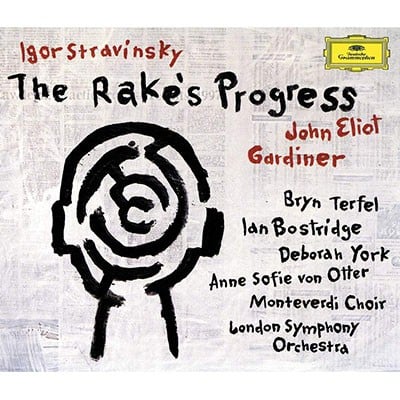

Ian Bostridge/Deborah York/Bryn Terfel/Anne Sofie von Otter/Peter Bronder/Anne Howells/Martin Robson/Julian Clarkson/

Monteverdi Choir/London Symphony Orchestra/John Eliot Gardiner

Deutsche Grammophon 4596482