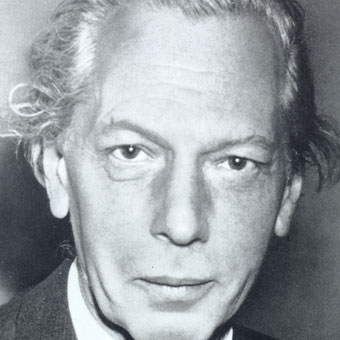

Boris Blacher

Memories of Boris Blacher

by Harald Kunz

He wrote twelve operas, ten ballets, fifty orchestral works, oratorios and concertos, numerous choral works and music for voices and instruments, chamber music, and at least a dozen electronic compositions. He was booed and cheered, attacked and revered. He worked until the last day of his life and, after his seventieth birthday, spoke of himself in the imperfect tense – „I was a modern composer once.“ It had become his habit to view himself and the world with irony.

It is easy to see Blacher as the „classic modern composer with the light touch“ because most people know him for those instrumental compositions, written with style and élan, only seemingly light yet entertaining in the best sense of the word, which established his world-wide reputation. Yet Blacher had written other works, like Großinquisitor and Requiem, Rosamunde Floris and Romeo und Julia, Drei Psalmen and Orchesterfantasie, that never failed to communicate their seriousness to the audience. These were the works that were most dear to Boris Blacher and they were essential to him in a way that the others, which are generally associated with his name, were not.

If asked about the chances of a new work, he used to say, „Patience! You can't calculate success“ or „Time is a merciless measuring device that does not allow much to survive. I am fortunate because I have written two high-class lollipops, Paganini-Variationen and Concertante Musik; I might get to live a while because of them.“ He also said, „If there were a recipe for success, then all we would hear would be ‘successful’ pieces.“ The thought appeared to make him uncomfortable.

„I consider myself to be one of those composers who do not follow a single path but, according to whether it brings me pleasure, sometimes compose in this way and sometimes in that: light or serious, entertaining or experimental.“

Blacher certainly took great pleasure in experimenting. This began already in the 1920s with the Dadaistic opera Habemeajaja. The high point was reached with music for Werner Egks meaningless but emotive artificial words in his Abstrakte Oper Nr. 1, which initially caused a scandal but went on to be a success. The end point was Ariadne, a duo-drama in which two speakers recite a text written in Goethe's time to an accompaniment by electronics in microtones of a third.

He also found great pleasure in jazz. Jazzy syncopation in Concertante Musik had made him unpopular with the Nazi press and later compositions often use chords that recall Blacher's liking for the Glenn Miller Sound of the 1940s. From time to time he wrote compositions for jazz ensembles like the Modern Jazz Quartet and the German All Stars. Blues Espagnola und Rumba for the twelve cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra demonstrates how elegantly Blacher combines jazz elements with the classical tradition.

Biographical reminiscences can be heard in the works employing Russian or Jewish motifs: the operas Fürstin Tarakanowa and Zweihunderttausend Taler, Parergon zu Eugen Onegin and the clandestine homage to Tchaikovsky, Poème for orchestra, and, of course, his early work Streichtrio über jüdische Volkslieder. The themes of his origins accompanied Blacher his whole life.

The creativity of the musician Blacher was guided and controlled by the rationality of Blacher the mathematician. According to the laws of mathematics, he constructed his compositions and created the rhythmic serial principle of his „Variable Metrics“. Yet even in the most logical of his scores, there are always deviations from the norm, breaks in the rules; Blacher said of such „mistakes“ that they are what renders art human.

Intelligence and imagination, charm and humour, nonchalance and understatement were the hallmarks of his personality. With these congenial traits in his music, Boris Blacher's oeuvre will remain timeless and contemporary.

(translation: Gloria Custance)